You see better when you're scared

Everyone gets scared sometimes. Maybe thunderstorms make your heart beat faster. Or maybe your mouth goes dry when your boss announces an unexpected meeting, or your palms sweat when it's your turn to give your report in front of unknown people. Perhaps you get butterflies in your stomach when it's your turn at the competition.

We all have fears from time to time. Fear can even be good for you sometimes and even help you stay healthy. Fear of getting too close to a campfire may save you from a bad burn. And fear of getting hit by a car makes you open-eyed while passing the street.

Some people even enjoy being a little scared. That's why they like to watch scary movies or go on roller-coaster rides or do bungee jumping. But what's going on with our body while we are afraid? What is adrenaline and why do we need it?

"FIGHT OR FLIGHT"

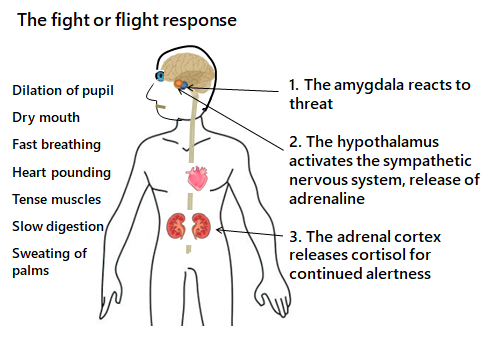

The body's reaction to fear is called the "fight or flight" response. And people have had it since the beginning of time.

Here's how it works. Imagine you're a caveman or cavewoman living 100,000 years ago - and you come face to face with a hungry saber-toothed tiger. You have two choices:

1) Run for it (that's flight), or

2) pick up your club and battle the tiger (that's fight).

In response to acute stress, the body's sympathetic nervous system is activated due to the sudden release of hormones. The sympathetic nervous systems stimulate the adrenal glands triggering the release of catecholamines, which include adrenaline and noradrenaline. This results in an increase in heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate.

Some of the physical signs that may indicate that the fight-or-flight response has kicked in include:

Rapid Heart Beat and Breathing: The body increases heartbeat and respiration rate in order to provide the energy and oxygen to the body that will be needed to fuel a rapid response to the danger. (Gordan R, Gwathmey JK, Xie LH. Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(4):204-14. doi:10.4330/wjc.v7.i4.204)

Pale or Flushed Skin: As the stress response starts to take hold, blood flow to the surface areas of the body is reduced and flow to the muscles, brain, legs, and arms are increased. You might become pale as a result, or your face may alternate between pale and flushed as blood rushes to your head and brain. (Kantorovich V, Eisenhofer G, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma: an endocrine stress mimicking disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1148:462-8. doi:10.1196/annals.1410.081) The body's blood clotting ability also increases in order to prevent excess blood loss in the event of injury.

Dilated Pupils: The body also prepares itself to be more aware and observant of the surroundings during times of danger. Another common symptom of the fight-or-flight response is the dilation of the pupils, which allows more light into the eyes and results in a better vision of the surroundings. (Chen Y, Lyga J. Brain-skin connection: stress, inflammation and skin aging. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2014;13(3):177-90. doi:10.2174/1871528113666140522104422 )

Trembling: In the face of stress or danger, your muscles become tense and primed for action. This tension can result in trembling or shaking. (Kantorovich V, Eisenhofer G, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma: an endocrine stress mimicking disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1148:462-8. doi:10.1196/annals.1410.081)